I sat in my former principal's office and told him I wanted to stop grading.

Needless to say, it required some convincing.

Fortunately, I had researched, planned, and prepared enough that he was willing to give me a shot. So, for the next year, I taught my freshman English classes without grading a single assignment.

Fast forward to June, and it was the most insightful and transformative (but also challenging) year of my career.

I know why you’re scared to give up grades in the classroom

When teachers hear about the idea of not grading students, there are several common, valid objections.

“My district requires us to give grades on the report card.”

For the sake of transparency, I had to do this, too. I couldn't get around putting grades on my students’ transcripts.

However, as I'll explain, these grades were only for each quarter and the end of the year. Additionally, the students decided what grade they deserved.

If you’re thinking that you should stop reading right now because you could never give up grades, then you’re actually the person I want to talk to: I’ll give strategies a little later on about what you can still take away from my experience, even if you absolutely can't or don’t want to give up grading.

“How will the students know how they’re doing?”

Without grades, you'll find ways to show and tell students directly how they're doing instead of obscuring that information with a number or letter.

Compare this: “you supported your argument with relevant, well-explained evidence.

To this: “B+”

And for those who say, “why not both?” I’d respond, which of those two pieces of information are students going to focus on? The grade? Or the feedback? We both know the answer.

In fact, an often-cited study showed that when students receive both grades and feedback, “grades were shown to decrease the effect of detailed feedback.”

Additionally, in a no-grades classroom, students develop the skills of autonomy and reflection as they learn to evaluate their own progress compared to expectations and exemplar work.

“Won’t the parents give me a hard time?”

Like you, I’ve read the parent emails and lived to tell the tale! In other words, I understand this is a valid concern.

However, when I shared my policies and reasoning behind my no-grades classroom during back to school night, parents were supportive, and some were even excited for the new approach.

Additionally, I developed correspondences with several parents throughout the year specifically because they saw qualitative feedback about their child's progress, and reached out to discuss it more.

While you may have other concerns, those are the three common ones I’ve encountered. With those out of the way, let’s take a look at how my no-grades classroom worked. Then, I’ll share the five lessons every teacher can learn, whether or not you ever want to teach without grades.

Teaching without grades: how does it actually work?

Here’s the high-level overview of the system:

- The class relied on feedback and reflection, instead of grades, to evaluate progress

- Clearly defined learning goals and exemplar work were essential for students and the teacher to stay on track

- Without grades, students had more freedom in how they showed growth using topics or media of their choice

- Each quarter, students built a small portfolio and made their case for their final grade in a conference with the teacher

As I mentioned, students received grades for each marking period and at the end of the year. However, no essay, homework, reading questions, quiz, etc. received a number or letter on it.

Instead, we used feedback and reflection to measure progress and evaluate students’ work. This process can work in any class with clearly defined content and skills goals.

Each quarter, students had to know which skills and content they were expected to learn and what it would look like if they were succeeding (this often involved the use of exemplar work). Preparing for this led me to get comfortable with my state's standards for English language arts. At the beginning of each quarter, we reviewed this information and students recorded the expectations in the form of “I can…” statements.

From there, we did multiple assignments and practice activities related to the reading, writing, speaking and language expectations for the quarter. Additionally, we set independent reading goals after calculating students’ reading speeds, with a method from teacher/author Penny Kittle.

The great part about this process was that after this information was laid out, the students and I had lots of freedom for how to achieve these goals.

If students wanted to demonstrate growth in informational writing by composing a guide to a favorite hobby instead of following the essay prompts I had suggested, they could do it. Additionally, If students wanted to redo an assignment, they could do it.

Throughout a typical week, students would show me finished or in-progress writing pieces, reading responses, annotations, recordings of themselves speaking, etc. I recorded feedback about their work in the gradebook. The students used this feedback to revise their work and parents used this to see how their child was progressing.

End of quarter portfolios and conferences

The best part came at the end of each quarter, where we followed this process:

- About two weeks before the end of each marking period, the class reviewed the expectations for the quarter and the related assignments.

- Then, students finalized and gathered their best work to show how they had met those expectations and organized them into a simple digital portfolio on Google Drive.

- Next, students completed a written reflection that explained the extent to which they met the expectations of the quarter.

- Lastly, each student had a short conference with me, where they presented what they believed their grade for the marking period should be and why.

Read: Space Type Use Case: Student Led Conferences

Students also created a larger, cumulative portfolio, sometimes called an “exit portfolio,” at the end of the year.

In about 90% of cases, the students’ choice of grade remained. Interestingly, some students were too self-critical and made their grade clearly too low. The rarest case was the student who lacked self-awareness and overtly gave themselves an A after completing little work or making little progress. That didn’t happen as often as you might think.

No, it wasn’t perfect: the challenges of going gradeless

Don't get me wrong, there were hurdles throughout this process. Some were resolved on their own or after a little effort, and others lasted all year. These were the major challenges:

- I had to rely on intrinsic motivation much more. This is part of the reason why student choice in reading and writing was an essential aspect of the class. Without the intermediate grade to motivate students, choice became a motivator.

- Allowing students to redo work caused confusion with parents and guidance counselors. Although I wanted students to redo their work throughout the year, to truly make the focus on improvement, this created some extra work or confusion on the part of parents and counselors.

- Some students put off completion of their work until the end of the marking period. They then recognized that this was not a good routine for them to follow. Because they missed out on the chance for me, and their peers to provide them with feedback and help them progress.

Not for you? You can still learn from teaching without grades

These are the five lessons that I gained from this year that any teacher can apply to their teaching, whether or not they ever decide to use a system of teaching without formal grades.

1) Teach students to reflect in a way that leads to growth.

As I mentioned, at the end of each marking period, students had to reflect on expectations and argue how they did or did not meet them. This was a specific, focused type of reflection that all classes can introduce at some point.

Often, teachers ask students to broadly reflect on how they did on a specific project, assignment, or time period without tying that reflection back to expectations, standards or exemplar work.

When the reflection process becomes more clear and focused, reflections become a way of students giving themselves actionable feedback, which is a truly powerful lever for learning.

Additionally, when you understand what it takes for students to reflect in a critical way on their own work, it will sharpen your ability to give students meaningful feedback.

2) Help students see what they’re supposed to be learning.

Whether you’re teaching with grades or not, the value of planning and articulating what students should be able to do and know is priceless. This then becomes the foundation of encouraging deeper reflection and more focused feedback.

This process can even happen within a more choice-based or student-driven classroom, such as one based around project-based learning or problem-based learning. In that situation, students can still be expected to articulate the questions they are pursuing or the problems they are solving. Prioritization is a real-world skill applicable to any classroom.

3) Use systems, not more effort, to make teaching sustainable.

If I had simply relied on collecting students physical papers, giving them feedback, then having them do a second draft, etc., this year would have been unsustainable. Instead, I used a few daily or weekly systems basis to make the feedback process easier.

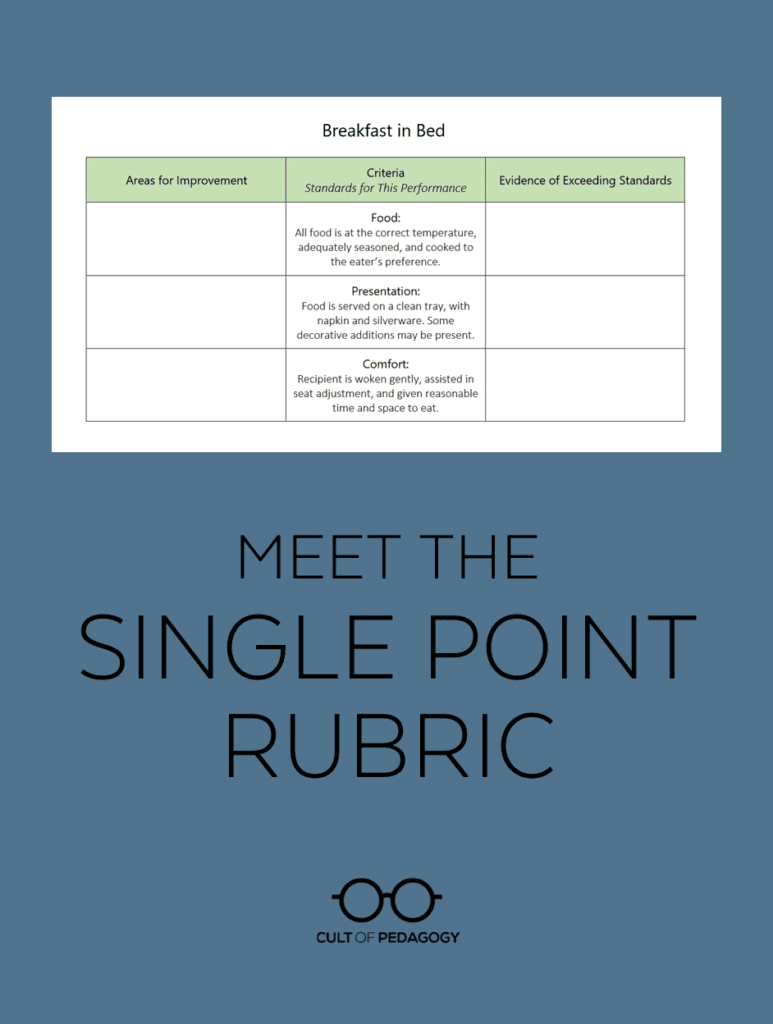

Feedback system: Jennifer Gonzalez’s “single-point rubric.”

Learn more about the single-point rubric at the Cult of Pedagogy.

There were three great benefits of using this as the one rubric for assessing student work:

- Time: By using one rubric over and over, it saved me time in creating the rubric and explaining it to students.

- Reflection: The double benefit here is that the rubric also serves as a place for the students to reflect on their work.

- Creativity: Because the “exceeds expectations” section of the rubric is blank, it opened up possibilities for creative ways students could exceed expectations on their work.

Feedback system: the Daily Record

Another feedback system I used was the Daily Record. This was a roster students filled out to share their plans for the day. I eventually modified this process so that it also included a specific goal that students were trying to meet during that class period.

This allowed me to focus on the students who might need more urgent help on that day. It also acted as an accountability measure. The act of writing down their goal for the day and seeing me check in on them at the end of class a few times urged some students to stay more focused.

Feedback system: Powerful Digital Tools

Last was the use of digital tools to give more robust, actionable feedback in a faster and more enjoyable way. At first, I used the Voice Memo app on my iPhone to record audio feedback to students, even if I was on hall duty and away from the computer.

Legendary English Teacher Jim Burke first gave me the idea of using the iPhone Voice Memo app to give students feedback with this Tweet almost 9 years ago.

I used tools like Kaizena and Formative to give feedback on student writing and reading assignments, which saved me time, but also made the process more enjoyable. Now, a tool like SpacesEDU allows teachers to have students gather their work in a digital portfolio and give real-time feedback on the work by commenting and messaging in the app.

4) Clearly state (even just for yourself) your teaching philosophy.

This process taught me about the value of having convictions about my teaching.

It is easy to float through the days, semesters and years of teaching, simply relying on momentum. But for this no-grades experiment, I had to be keenly aware of what I was doing and why I was doing it.

First, this was because I didn't have the crutches like a “gotcha” quiz or other ways to penalize students with bad grades. Additionally, I had to articulate my plans to colleagues, administrators, or parents I worked with that year. This required me to go to academic literature and reach out to other teachers who had taught in a similar way.

This brings me to my last point...

5) Find a community of educators to support your growth.

When teachers try something new, it can feel isolating. At times, new approaches are met with mixed messages by others in education.

Fortunately, during my no-grades journey, I discovered the Teachers Throwing Out Grades Group. This was an incredible resource for me throughout the year. There were also specific educators, including Starr Sackstein, Joy Kirr, and Mark Barnes, amongst others, who shared their knowledge, experiences, and time to help me get through the process.

Regardless of where you are in your teaching career, you can find an online community of educators where you can ask questions, get resources, or find help.

Gradually, education is breaking away from the rigid vision of grades, bells, and other inflexible relics of the past.

I encourage teachers to examine the way you assess your students and consider how you can explore ways to put feedback ahead of grades, delay grades, or use a digital portfolio system like SpacesEDU to emphasize learning over grades.

If you're in a place where that's not possible, then I hope that you can embrace the five lessons I’ve shared as ways to make learning more of a focus in your instruction, and importantly, to make teaching more sustainable and even fun.