If you work in education long enough, you will likely hear someone marvel at complexity. It sounds like this, “Yes, we definitely need to rethink our grading practices, but it’s just so complex.” When people say this, they are inferring that change is impossible amidst the many intersecting interests in education today. Transformation is always possible, but it requires a deeper understanding of the research into change management. This blog outlines why change management is important in K–12 education and explores how school districts can leverage change management strategies to support educational transformation.

Why is Change Management Important in K–12 Education?

Without an understanding of change management, well-intentioned initiatives are likely to become another addition to the graveyard of good ideas that died during implementation. When change is not managed well, the initiative is seen as a top-down mandate that stakeholders will appear to comply with on the surface. However, they are often stalling long enough for the next initiative to come along. But, when change is managed effectively, we can embed a process of continuous improvement that will continue long after the initial catalyst is gone.

To understand effective change management, we need to first acknowledge that change is hard, especially in education. Organizational psychologist, Adam Grant, points out in Think Again that we’re biologically programmed to stick to what we know:

“Yet there are also deeper forces behind our resistance to rethinking. Questioning ourselves makes the world more unpredictable. It requires us to admit that the facts may have changed, that what was once right may now be wrong” (pp. 4).

This quote is profound in the context of education as everyone who enters this profession believes they are doing what’s best for kids. To suggest change is to challenge this intention. As well, every member of our community has had their own experiences in school. This makes it hard to move forward according to research-validated evidence.

Building a Vision for Transformation

Though the barriers in K-12 education are intimidating, research into change management teaches us how to create a vision that will move people away from the status quo. One of the most cited researchers in this area is John Kotter. He studied change across many organizations to land at eight critical steps to successful transformation. To create a vision, Kotter describes that a senior leader must first communicate a sense of “urgency for change.”

- What is possible for students, teachers, and society?

- What urgent problems need solving to reach that vision?

- What is the price of inaction?

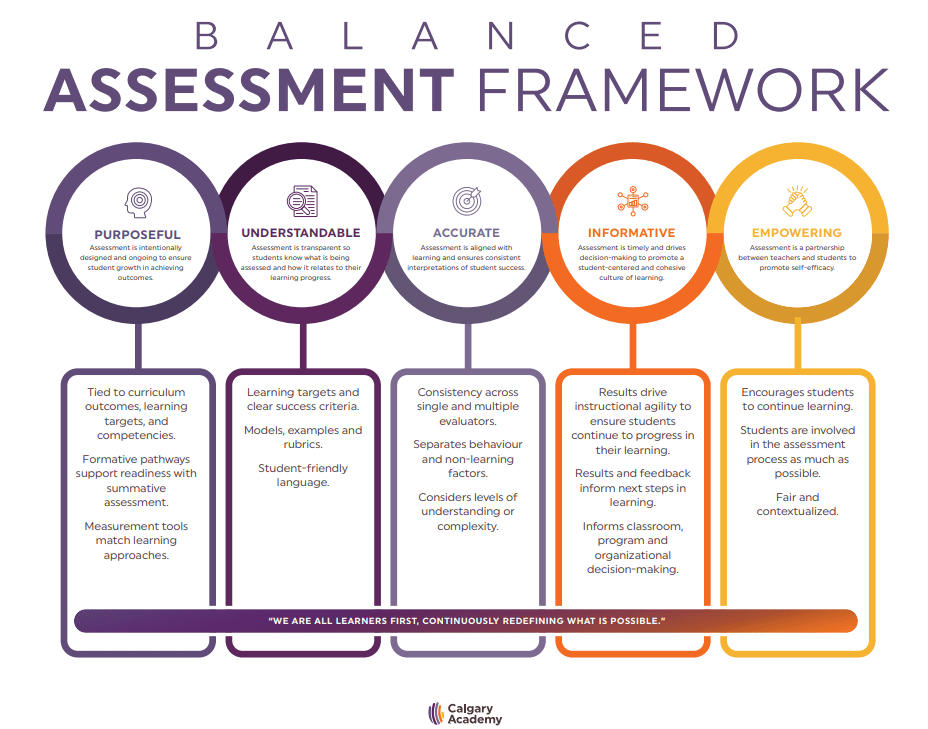

After communicating a sense of urgency, the next step is to “establish a powerful guiding coalition” that represents a diversity of perspectives. It is this team that creates a compelling “vision for change.” It might be a list of guiding principles, a framework, a model, etc. Whatever format it takes, it must be an intuitive tool to guide implementation.

Example of a Change Management Vision

Balanced Assessment Framework (Calgary Academy)

Leadership in Educational Change

Once the vision is established, leadership becomes critical to implementation. However, the definition of leadership in this context extends far beyond those with supervisory responsibilities. While district leaders maintain a sense of vision and urgency whenever they communicate to stakeholders, it’s a distributed leadership approach that will spread ideas like a virus until a tipping point.

In his research, Kotter refers to this critical stage as “empowering others to act within the vision.” One way to spark distributed leadership is to create action teams of teacher leaders to design the implementation of the vision within their contexts. For instance, a shift towards standards-based grading might engage action teams to determine the reporting standards for a particular subject across their division. Another way to spark informal leadership is to hold space for stories of innovation during PD days and staff meetings.

Engaging Stakeholders in the Change Management Process

Once the vision is established and leadership is distributed, it becomes important to engage key stakeholders. Engagement with families is most successful when it is invitational, rather than explanatory. For instance, rather than only communicating with parents once the change is enacted, engage them before implementation to build capacity and seek feedback. This can be done by inviting them to panels featuring leading experts, surveying them around the elements of the vision, and inviting them to join focus groups for a more in-depth understanding of their perspective. The same goes for students. An important consideration in stakeholder engagement is to also design focus groups that invite and amplify marginalized voices in the community to ensure equity (Safir & Dugan, 2021).

Data-Driven Decision Making

The early stages of implementation will provide the most important information for continued decision-making. When it comes to teachers deciding whether to buy into this new idea, evidence of impact is what will shift their mindset (Guskey, 1986). They need to see that this change will be a better practice for student learning.

Kotter refers to this phase of the implementation journey as “planning for and creating short-term wins.” This win is often planned by the guiding coalition as they engage with all stakeholder groups, including teachers. An example of an early win in a district looking toward grading reform was the removal of four reporting periods in exchange for one linear grading period per year. Many stakeholders felt the chunking of learning into quarters was artificial and made it hard to accurately describe the learning journey from September to June.

Overcoming Resistance to Change

Of course, despite our very best efforts to engage and include all members of the community in change, there will be vocal resistors. How do we get them on board? To return to Adam Grant’s research, “Psychologists have long agreed that the person most likely to change your mind, is you.” This means we can’t enter conversations with resistors trying to change their minds, we can only create the best conditions for them to do so on their own. Grant suggests several strategies to achieve this:

- Find the steelman in their argument. What aspect of their concerns can you validate and agree with?

- Ask questions with genuine curiosity. We want to help them explore the nuances of their own thinking.

- When the opportunity presents itself, offer only one potent point. Research shows that our influence goes down with each subsequent point we include.

Implementing Sustainable Change Initiatives

Research into change management demonstrates it takes 3-5 years for an organization to successfully navigate implementation (Learning Forward, n.d.). Though change can take five years, many organizations reach a tipping point in three years. However, a critical part of the implementation journey at this tipping point is to ensure processes and routines are in place to support sustainability. This marks the difference from an initiative being just another “thing” to it becoming an integral part of a culture. This might look like embedding the change into existing structures, such as using collaborative team meetings in a PLC to embed standards-grading principles, or creating new ones, such as building an accessible digital space to organize rubrics and instructional materials as teachers implement standards-based learning.

Addressing Common Pitfalls

Throughout the change journey, there are many common pitfalls to avoid. First, we often forget that change is more emotional than clinical. Even the most detailed implementation plans and data analysis will fall flat if we forget this truth. A common mantra my colleagues and I use in our work is, “urgency with ideas, patience with people.” While the district leader must communicate passionately about the vision, that passion cannot be misguided toward hasty implementation.

Another common pitfall is to let the loudest resistors stall the change process. In any intervention, we can predict that 5-15% of folks will need a more targeted or personalized approach (Lewis, Sugai & Colvin, 1998). Often, the reason these folks are in a leader’s office loudly protesting is they know they are the outliers. They’re feeling desperate. We can listen to them empathetically, and look for the steelman, but remember there is a quieter 80% who are curious and waiting for the next steps.

Celebrating Success and Continuous Improvement

There is one critical piece of the journey to educational change that is often forgotten – celebration. Assessment expert, author, and consultant Katie White discusses the impact of celebration when she writes, “Everyone needs to feel like they are doing things right—making good decisions and accomplishing goals” (2021). How can we support each teacher to celebrate throughout the change journey? White suggests that celebration is most impactful within the cyclical process of self-assessment. She suggests a three-phase process that teachers can be supported through as well:

- Analysis and reflection

- Goal setting

- Celebrating growth

A critical note here is to ensure that goals are evidence-based in the context of the wider vision. When celebration is personalized and tied to evidence-based goals, it becomes meaningful.

Leading change in a complex system like education is challenging, but it’s not impossible. Think of managing change like driving a car along a country road in the dead of night. Our vision, like headlights, illuminates only the next 100 yards. This allows us to take one step forward and then the vision lights our path for the next one. Eventually, we will have traveled, step-by-step, to our destination.

Adopting a new tech tool in your school or district? Download this infographic on how to get educator buy-in.

References

- Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know. Viking, Penguin Random House; New York, New York.

- Kotter, J. (2012). Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Safir S. & Dugan J. (2021). Street data a next-generation model for equity pedagogy and school transformation. SAGE Publications.

- Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff Development and the Process of Teacher Change. Educational Researcher, 15(5), 5-12.

- Learning Forward. (n.d.). Standards for Professional Learning. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://standards.learningforward.org

- Lewis, T., Sugai, G. & Colvin, G. (1998). Reducing Problem Behavior Through a School-Wide System of Effective Behavioral Support: Investigation of a School-Wide Social Skills Training Program and Contextual Interventions. School Psychology Review. 27. 446-459.

- White, K. (2021). Student self-assessment: data notebooks, portfolios, and other tools to advance learning. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.